The Bots in BG are a big mega system built from many smaller subsystems. All of the little parts work together harmoniously to make the computer players smart, skilled, and life-like. A list of these systems is below:

- Environment & Enemy Scanning

- Situational Strategy-Patterned Brains

- Randomized Bots Difficulties

- Waypoint Navigation

- Context-Sensitive, Team-Based, Responsive Vcomms

- Population Manager

Environment & Enemy Scanning

Any player, real or artificial, needs to be aware of the constantly changing conditions on the battlefield. This is why BG’s bots need to scan the environs several times a second, to give it the information it needs to be able to react quickly and correctly.

A bot must ask itself these questions:

- Where is my nearest teammate?

- Is there a visible enemy nearby? Which is the closest? Which is the second closest?

- Which friendly flag is closest to me?

- Is there an enemy flag I could capture?

- Am I closer to the nearest enemy flag or the nearest enemy player?

- Am I outnumbered or surrounded?

- Are there any waypoints I might have to use soon to navigate the map?

What’s more, how often it asks itself these questions depends on its current situation. For example, a bot that is dead does not ask itself these questions, while a bot engaged in close-quarters combat receives a nearly constant stream of information. This helps improve performance and ensure quick-thinking is possible where it’s needed most.

Situational Strategy-Patterned Brains

In a battle in the American War of Independence, a soldier could find himself in any of countless possible situations. A good, experienced soldier has to be able to interpret the information he has and act accordingly. It has to know when to shoot, when to move forward, when to fall back to a teammate, how to capture a flag, and more.

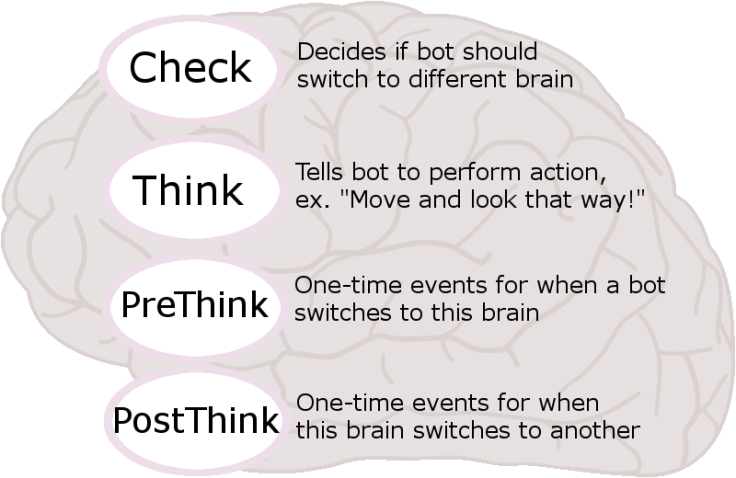

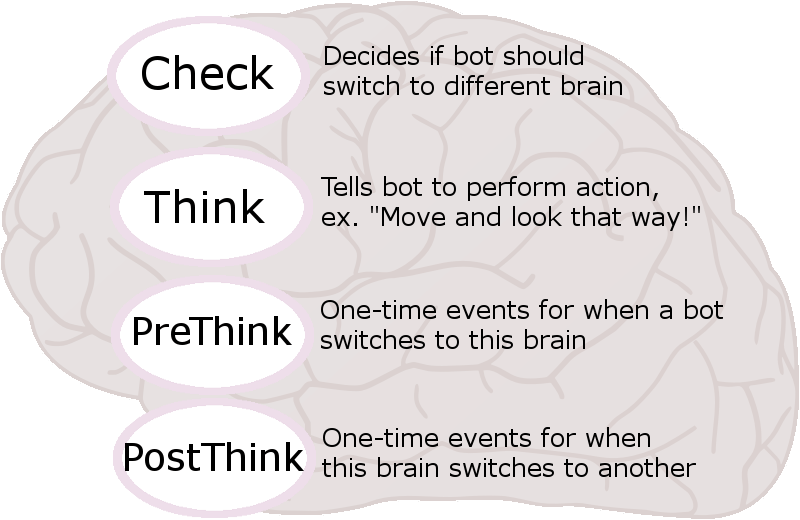

BG’s bots do all of this via a strategy pattern. That is, all of the bots have access to a “family” of interchangeable “strategies”. Each strategy is like a brain that can control any number of bots at any time. Here is a visualization:

Here is the outline of a brain as it is written in BG’s source code. There are also extra elements of a brain such as delay between thinks, a context which is sent to the vcomm manager (as described later), and a name for the brain.

struct BotThinker {

bool (CSDKBot::* m_pThinkCheck)(); //checks if a different thinker should be scheduled

bool (CSDKBot::* m_pThink)(); //called after every m_flThinkDelay

bool (CSDKBot::* m_pPreThink)(); //called when this think is first scheduled

bool (CSDKBot::* m_pPostThink)(); //called when another event is scheduled

float m_flThinkDelay; //delay between each think

BotContext m_eContext; //context sent to vcomm manager when this brain is scheduled

const char * m_pszThinkerName; //name of this brain, helpful for live debugging

};

So, the bots know what a brain is. But how many different brains are there, and what do they actually do? Here is a short list.

- Waypoint – As long as a bot is alive and their are no nearby enemies or flags, a bot uses this brain to travel between manually placed waypoints on the map.

- Flag – When a bot sees a capturable flag and there are no enemies in the way, a bot will move to the flag and capture it.

- Long Range – When a bot sees an enemy from far away, the bot moves straight toward the enemy. It may or may not also shoot.

- Medium Range – In medium range combat, a bot dances around in a generally forward direction, always looking at the closest enemy or enemies. It is likely to shoot at this distance. Also at this range, a bot will always move forward if its nearest teammate is already in melee.

- Melee – In close-quarters, a bot will dance around erratically and stab enemies which are close enough. It is likely to fire its musket if it hasn’t already.

- Retreat – If at any time in medium range combat a bot decides that it is outnumbered and there is a teammate nearby, it will turn around and fall back to the teammate.

- Point Blank – this is the brain a bot uses whenever it wants to shoot. The bot stops, may or may not aim down sights, may or may not crouch, points itself at an enemy, waits for a short time, and then fires its weapon. It is more likely to aim at longer ranges than short ranges.

Randomized Bot Difficulties

BG’s bots have different difficulty settings. The difficulty is controlled by a server-side console variable, bot_difficulty. The tooltip for it is “Bot skill level. 0,1,2,3 are easy, norm, hard, and random, respectively.”

The difference between the difficulties lies in seven different stats:

- Aim Randomness – higher values decrease accuracy of looking around.

- Reload Tendency – harder bots don’t reload as often.

- Long Range Firing Tendency – harder bots save their bullet for close-range.

- Turn Speed – harder bots turn faster.

- Bravery – harder bots don’t retreat as often.

- Melee Range Offset – the best bots have a better sense of their own melee range.

- Melee Reaction – how quickly bots react to new melee targets.

There are three difficulties – easy, medium, and hard. On the “random” bot_difficulty setting, medium bots are the most common while easy and hard are less common.

Also, the difficulty of the bots also affects the ranks given to them in their names. They are as such:

- Easy – Private, Lance Corporal

- Medium – Private, Lance Corporal, Corporal

- Hard – Corporal, Serjeant (that is an old-fashioned spelling)

Rarely, a Hard bot may spawn with an officer’s rank (Lieutenant, Captain, Major, Lieutenant Colonel) and a special name!

Waypoint Navigation

When there are no enemies or flags around, the bots need to know how to navigate the level. They do this with their “waypoint” brain, which points and moves them toward the closest waypoint. When the bot reaches the waypoint, the waypoint itself decides where the bot should go next.

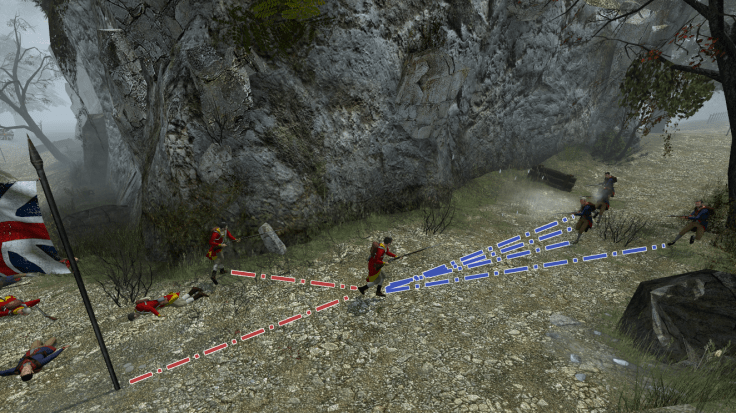

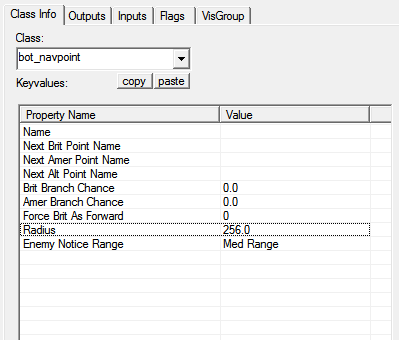

For example, if a British bot enters the town square on bg_townguard (as pictured above), the waypoint on the corner decides if the bot should go one way or the other. This allows the bots to “branch” onto different paths.

Also built into this system is that each waypoint has a “radius” which controls the tightness of the waypoint. Smaller values are for chokepoints, while larger values are for open areas. Using these larger values allow the bots to move more fluidly rather than just connecting the dots in straight paths.

All of these options and more are wrapped into the scripts for the new bot_navpoint entity:

It can be a lot of work to set up these points, as each point has to be given a name and manually linked to the other points. Yet once they’re all networked together, the results are beautiful and fun!

Context Sensitive Vcomms

Have you every played Counter-Strike and told a bot to follow you, just for them to say “No”? Just as much, the bots in BG can communicate with you too. Now, they won’t change their actions based on what you tell them (yet?), but they will still utter their own messages and respond to yours. All of this is part of BG’s Vcomm manager.

Every 15-20 or so seconds (randomly), the Vcomm manager picks a bot to give a message and tells the bot to give that message. But how does it know which bot to pick and which voice command the bot should say?

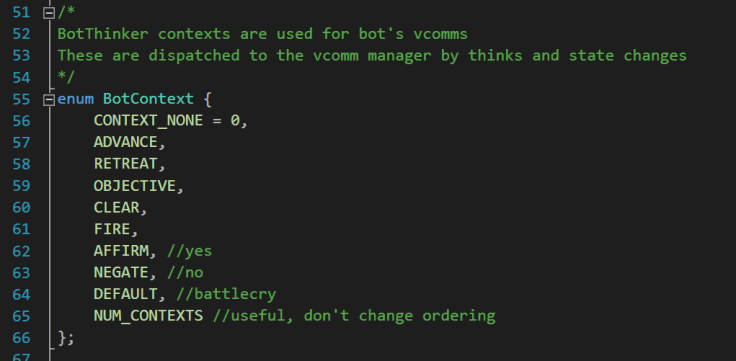

If you scroll up and look at the C++ code for a bot brain/thinker/pattern, you will see the line “BotContext m_eContext”.

That’s because whenever a bot switches to a new brain, it notifies its teams’ Vcomm manager of this. So that when the Vcomm manager decides to have a bot do a voice command, it will have a context that reflects recent events in battle and it will know which bot those events are happening to.

These are the different “contexts” that can be sent by the brain:

But how do the bots respond to the player and to each other? Well, whenever anyone does a voice command, the team’s Vcomm manager is also notified of this. Then it will randomly (about 30% of the time) decide that in this case, the next message to be played by a nearby bot will be in 3-5 seconds and that the bot’s message will depend on what the other player’s message was.

All of this works out to where you could have a bot start retreating and say “Fall back!”, but then his bot teammate says “No way, sir!”, and then when the two are rejoined they start pushing forward again.

Simple, yet effective at making the battlefield and the bots feel more real!

Population Manager

The Bot Population Manager is always running. Every 10 seconds it checks these server-side console variables to add or remove bots as necessary:

- bot_minplayers – Default number of bots if bots are enabled.

- bot_minplayers_map – Map specific recommended number of bots. This will be larger on larger maps and smaller on small maps. This setting will be in each map’s CFG.

- bot_maxplayers – When the total number of players exceeds this amount, start kicking bots.

- bot_minplayers_mode – 0 bots disabled, 1 use bot_minplayers, 2 let bot_minplayers_map override, 3 use only bot_minplayers_map.

Also, there is a handy console command, bot_kick_all, which will remove all bots and set bot_minplayers_mode to 0.

Using these settings, it’s easy for a server to control its bot population even when there are no admins present!

Looking Forward

Wow! These bots really do play well. Yet, there are always improvements to be made. It was all built to be very modular, so that new brains can be added to do new things. More Vcomm contexts can be added and the logic updated to have more complicated conversations. Maybe even, a player’s command could even change the brain of the bots, so that “Follow me!” would make the bots follow the commanding player, or a “Fire!” command would tell all the bots to fire!

Happy trails! Here’s to the future.

1 Pingback